May 16, 2022 | MIT researchers have created a portable desalination unit that can automatically remove particles and salts simultaneously to generate drinking water. The user-friendly unit weighs less than 10 kilograms and does not require the use of filters.

Text source: Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The suitcase-sized device, which requires less power to operate than a cell phone charger, can also be driven by a small, portable solar panel. It automatically generates drinking water that exceeds World Health Organization quality standards. The technology is packaged into a user-friendly device that runs with the push of one button.

Unlike other portable desalination units that require water to pass through filters, this device utilizes electrical power to remove particles from drinking water. Eliminating the need for replacement filters greatly reduces the long-term maintenance requirements.

This could enable the unit to be deployed in remote and severely resource-limited areas, such as communities on small islands or aboard seafaring cargo ships. It could also be used to aid refugees fleeing natural disasters or by soldiers carrying out long-term military operations.

Research paper

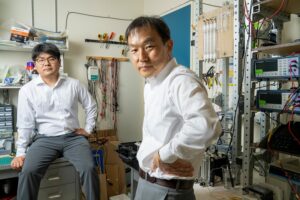

“This is really the culmination of a 10-year journey that I and my group have been on. We worked for years on the physics behind individual desalination processes, but pushing all those advances into a box, building a system, and demonstrating it in the ocean, that was a really meaningful and rewarding experience for me,” says senior author Jongyoon Han, a professor of electrical engineering and computer science and of biological engineering, and a member of the Research Laboratory of Electronics (RLE).

Joining Han on the paper are first author Junghyo Yoon, a research scientist in RLE; Hyukjin J. Kwon, a former postdoc; SungKu Kang, a postdoc at Northeastern University; and Eric Brack of the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command (DEVCOM). The research has been published online in Environmental Science and Technology.

Senior author Jongyoon Han, right, pictured with first author Junghyo Yoon, seated (Photo: M. Scott Brauer).

Filter-free technology

The unit relies on a technique called ion concentration polarization (ICP), which was pioneered by Han’s group more than ten years ago. Rather than filtering water, the ICP process applies an electrical field to membranes placed above and below a channel of water. The membranes repel positively or negatively charged particles − including salt molecules, bacteria, and viruses − as they flow past. The charged particles are funneled into a second stream of water that is eventually discharged.

The process removes both dissolved and suspended solids, allowing clean water to pass through the channel. Since it only requires a low-pressure pump, ICP uses less energy than other techniques.

But ICP does not always remove all the salts floating in the middle of the channel. So the researchers incorporated a second process, known as electrodialysis, to remove remaining salt ions.

Field tests

After running lab experiments using water with different salinity and turbidity (cloudiness) levels, they field-tested the device at Boston’s Carson Beach.

Yoon and Kwon set the box near the shore and tossed the feed tube into the water. In about half an hour, the device had filled a plastic drinking cup with clear, drinkable water.

The resulting water exceeded World Health Organization quality guidelines, and the unit reduced the amount of suspended solids by at least a factor of 10. Their prototype generates drinking water at a rate of 0.3 liters per hour and requires only 20 watt-hours per liter.

Funding

The research was funded, in part, by the DEVCOM Soldier Center, the Abdul Latif Jameel Water and Food Systems Lab (J-WAFS), the Experimental AI Postdoc Fellowship Program of Northeastern University, and the Roux AI Institute.

Further information

The full-length article is available at the MIT’s website.